History

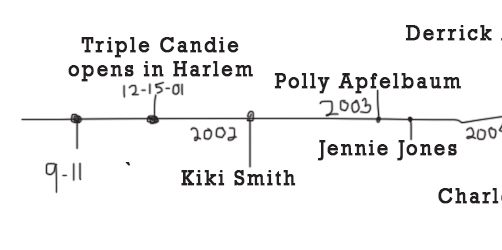

Triple Candie received its business license on September 12, 2001 — the day after the attacks on the World Trade Center. It opened its doors to the public on December 15, 2001, joining Christian Hayes' The Project as one of the few art spaces in Harlem and becoming the first new, large-scale space in the neighborhood since the Studio Museum in Harlem was founded in 1969. From the outside, its building — a former brewery, with few windows — looked abandoned. Visitors entered through a grey garage door, ascended a short flight of wooden stairs, and emerged into a brighly lit, 5,000 sq. ft. gallery with soaring cast-iron columns, weathered brick walls, and an expansive, off-white, painted concrete floor. For many, the interior was reminiscent of Soho alternative spaces of the 1970s.

Presenting Not Producing, 2001–2

Founded by two art historians with experience in museum education and a regional art center, Triple Candie was initially conceived as a presenting rather than a producing venue. The idea was that the gallery would curate none of the exhibitions it presented. Instead, it would invite outside organizations (primarily nonprofits, but occasionally commercial galleries) to produce or curate exhibitions for its facility, which Triple Candie would then promote and staff, and around which it would organize educational programs. The post-9/11 recession made such a strategy unsustainable. In fact, a month before Triple Candie was to open with a performance-installation by the artist Josiah McElheny, the Public Art Fund, which was producing it, canceled the show citing economic distress. Triple Candie opened nontheless, with two projects by outside organizations — The Jacob Lawrence Foundation hired Franklin Sirmans to curate an exhibition titled Rumors of War, and Pace Wildenstein Gallery organized a show by Kiki Smith. The strategy was abandoned after the second exhibition.

The Early Inter-generational Group Shows, 2002–4

For the next two years, Triple Candie organized group exhibitions, inspired by its Harlem location, and mixing the work of emerging and established artists. This ran counter to the prevailing tendency among nonprofit spaces at the time, which was to focus exclusively on emerging or un-represented artists. These exhibitions included Sugar & Cream: Large, Contemporary Wall Hangings (with work by Trenton Doyle Hancock, Jim Hodges, Rosie Le Tompkins, and others), I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (After Paul Laurence Dunbar) (with videos by Vito Acconci, Chris Marker, and Sara Sun), The Reality of Things (Robert Gober, Daniel Guzman, Sherrie Levine, Shinique Smith, et al), and Living Units (Ricco Gatson, Jessica Stockholder, Andrea Zittel, others). Though many of these shows required colloboration with commercial galleries and other nonprofits, during this period Triple Candie began maintaining an arm's length relationship to its colleagues. For example: Although Triple Candie was a founding member of the New Art Dealers Alliance (NADA) in 2002 it withdrew its membership within a year, after finding the organization's non-competitive and non-commercial rhetoric to be disengenuous.

Solo Projects, 2004–5

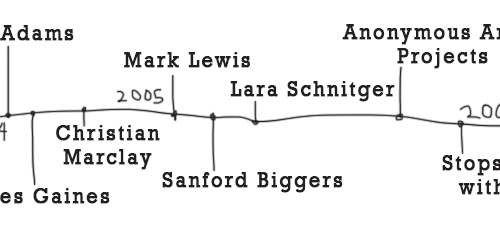

As Triple Candie saw other New York-based, nonprofit art spaces (Artists Space, White Columns) abandon their age-old focus on emerging artists, it changed its programming model again. For the next two years, the gallery focused almost exclusively on producing ambitious solo projects — many New York-debuts. These included projects by Sanford Biggers, Taylor Davis, Rashawn Griffin, David Humphrey, Brian Jungen, Mark Lewis, Rodney McMillian, Halsey Rodman, Lara Schnitger, Jennifer Stillwell, Heeseop Yoon, and others. It also presented a fifteen-year survey of the work of the influential Cal Arts professor Charles Gaines, for which it commissioned a major new, large-scale sculpture. When it could, Triple Candie provided the artists with generous stipends (up to $10,000), covered their travel and accommodations, secured fabrication assistants, and closes the gallery for as long as five weeks so that artists could develop their exhibitions on site, as if the gallery were their studios.

Slide Shows, 2002–5

During its first four years, Triple Candie also curated an annual series of artist talks (collectively titled "Slide Shows" and presented as exhibitions) that explored the various forms of rhetoric artists use to describe their practices. Participating artists included Laylah Ali, Tony Feher, Jon Kessler, Dana Schutz, James Siena, Amy Sillman, Phoebe Washburn, Kehinde Wiley, and others.

The Anonymous Artist Projects, 2004–5

In the summer of 2004, and again in 2005, Triple Candie produced The Anonymous Artist Project I and The Anonymous Project II. For each, it invited a well known New York artist to create a new work/installation that differed substantially from her/his/their other work, with the understanding that both the artist and Triple Candie would rigorously guard the artist's identity in perpetuity. For the artists, the shows provided a risk-free opportunity to experiment on a large-scale, in a beautiful space. For visitors, they prompted an understandable frustration; many felt unable to judge the work without information about the artists' backgrounds, though most assumed that the artists were of African descent, given the gallery's location. Visiting the second project, Philippe Vergne, then working at the Walker Art Center, noted: "Either the artist is highly accomplished or completely naive. I can't tell." Since then, other organizations have curated anonymous artist projects — e.g. Vienna Succession (2007) — but in most, if not all, cases the condition of artistic anonymity has been breached at the end of the show. The two artists who did these projects at Triple Candie remain, to this day, unknown.

Art-less Exhibitions, late 2005–8

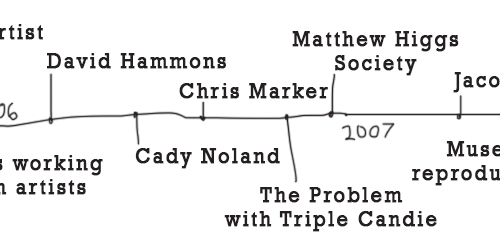

Triple Candie switched to its art-less model of exhibition-making in the winter of 2005-6. By then, with the art market booming and the art fair culture expanding, Triple Candie was having increasing difficulty competing with commercial galleries and major museums for artists' time and attention. Moreover, younger artists and those previously marginalized, were now gaining ready access to galleries and no longer saw nonprofit spaces as necessary or even relevant. The situation became most evident for Triple Candie when it set out to organize a major exhibition of new art made in Harlem. Artists known personally to Triple Candie with studios in the neighborhood — Ellen Gallagher, Julie Mehretu, Dana Schutz, and Nari Ward, among others — were at the time were struggling to keep up with their galleries' demands for new work and at best were only able to make available minor works. Triple Candie canceled the show.

Responding to its newfound institutional limitations (i.e. a relative lack of power, money, and social connections) and unable to lure artists away from the commercial market through generous stipends and ample space, Triple Candie arrived at an inflexion point: would it close, or would it yet again readapt to changing circumstances? It chose the latter. This time it developed a program model that wasn't dependent on artists, their galleries, or their collectors. This returned to the organization a curatorial freedom that had been lost. Triple Candiebegan producing exhibitions about art without the involvement of artists, and rarely containing art.

The first of these shows was a comprehensive retrospective on the art of David Hammons, realized with photocopies and computer print-outs, and without the artist's approval (David Hammons: The Unauthorized Retrospective). Though the exhibition was described as "arrogant" by one critic (David Cohen of The New York Observer was the first critic to see it and he was so insensed that he refused to write about it), the show received positve reviews in the New York Times and just about every English-language art magazine. David Hammons himself never came to see it in person. On the morning of the first day of the show, however, upon opening the gallery, staff members found a the board for a clown bean-bag toss leaning against the front door. When later asked by the New York Times for a response to the exhibition, Hammons replied by email, "no comment."

Triple Candie's second art-less show was conceived at the same time as the Hammons exhibition but realized several months later. The first survey ever of Cady Noland's art, it consisted of thirteen sculptural surrogates built by Triple Candie and four artists using incomplete information gleaned from the internet (Cady Noland Approximately: Sculptures and Editions, 1984-2000). All of the objects were therefore wrong, and the show as a whole presented a plausible charicature of an oeuvre. The press response contrasted sharply with that to the Hammons show. Jerry Saltz, then writing for the Village Voice, said that Cady Noland should hire a lawyer and "get medieval" on Triple Candie. Others wrote that the show raised interesting questions but told viewers nothing about Cady Noland's art. The artist herself never saw the exhibition.

For the next two and a half years, Triple Candie continued to make exhibitions in this vein. Many were retrospectives or surveys — such as Lester Hayes: Selected Work, 1962-1975, which focused on the work of a bi-racial post-minimalist artist (the artist was fictional), and Limelight: Gallery and Coffeehouse, 1954-1961, which focused on New York's first commercial photography-only gallery . Other shows focused on the misrepresentation of art by art museums -- such as Undoing the Ongoing Bastardization of the Migration of the Negro by Jacob Lawrence-- or misrepresentation in general — Flip Viola and the Blurs (Misrepresenting an artwork can create a non-art experience of comparable value). Still others presented objects borrowed from Harlem neighbors or scavanged from the streets outside the gallery -- Unwitting Accomplices: 36 Objects Thrown in Violent Incidentsand The Social History of Objects (After Spoerri and Nabokov).

Nine-Month Displacement, 2008–9

In December 2007, Triple Candie's landlord began extensive renovations of its building, beginning with the replacement of its facade. When noise, construction dust, and flooding made it impossible to program, Triple Candie exercised a 3-month escape clause in its newly negotiated five-year lease. Its parting show, Thank You For Coming: Triple Candie, 2001–2008, surveyed the gallery's first seven years through surrogates, reproductions, recreations, artifacts, and props. The New York Times cited Triple Candie's closing as one of the most significant "art" events of the year; alongside Philippe de Montebello's retirement, and the explosion of the Chinese contemporary art market.

Triple Candie vacated its facility on May 1, 2008 not knowing if it would reopen again. Five months later, the it signed a lease on an absolutely ruinous storefront in a residential neighborhood twenty blocks north of its first space. It spent more than 1,000 volunteer hours renovating it — installing a new ceiling, facade, floor, bathroom, lighting, and office area. The new Triple Candie opened on February 15, 2009.

The Changing Same: Two More Years in Harlem, 2009-10

For the next two years, Triple Candie curated a string of inter-related art-less exhibitions in its new space. Although the shows' theses varied considerably, many of the objects they contained remained the same. (Objects exhibited at Triple Candie generally have three fates when a show is deinstalled: they are discarded, they are given away to people from the neighborhood, or they are taken apart and their component parts are recycled and used in future exhibitions.) Some of the shows made use, again, of the survey or retrospective trope — Maurizio Cattelan is Dead: Life & Work, 1960-2009 being the best example. Some were fictious creations, such as The Calais Guild: Prayer Blankets — an exhibition proportedly about the work of a tiny textile group in Southeast Maine, but which was instead a forthright concoction of Triple Candie -- or Costume Jewelry that Scratches the Skin, about four fictitious editions publishers from Gateshead, U.K.; Genoa, Italy; Santiago de Chile, Chile; and Vancouver, Canada. Exhibitions based on real subjects either intentionally mis-represented, "improved upon," or commented on existing works by artists such as Lewis Baltz, Dexter Sinister, or Ryan Gander. Triple Candie also curated several shows that were self-referential: The Glass Menagerie (after Tennessee Williams), Two Character Play (after Tennessee Williams), and Beavers as Weavers, and Non-Believers.

Leaving Town and Another Hiatus, 2010

For nine years, Triple Candie operated as a completely volunteer-run enterprise. Funding for the gallery's activities came from outside employment, as well as grants and contributions. Ninety-percent of the budget was used for rent.

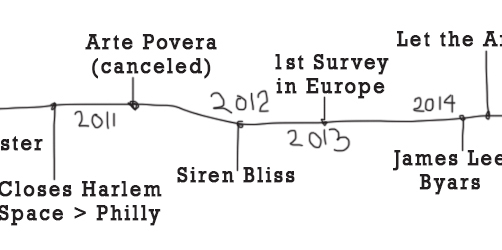

On December 31, 2010, Triple Candie closed its Harlem space and left New York City. The co-directors moved to Philadelphia, where one of them became a program officer at an art foundation. The upside was steady employment; the downside, severe conflict-of-interest restrictions by the foundation that forbade Triple Candie from curating in the Philadelphia region. It took a few years before Triple Candie was up-and-running again, this time as an exhibition-production agency that worked with museums in the U.S. and Europe.

Triple Candie On the Road & Paris Survey, 2011–14

Since 2011, Triple Candie has produced exhibitions at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art, Salt Lake City; Museum of Contemporary Detroit; and elsewhere. A project commissioned by Artissima in Turin, Italy, was cancelled three weeks before it was to open out of concerns that it would offend artists, dealers, and threaten the viability of the organization. The exhibition posited the non-existence of arte povera.

Triple Candie also

contributed projects to exhibitions at Le Musée de Moulages [Museum of Casts], Lyon, France; Le Musée de l'Objet, Blois; and Frac/Ile-de-France — Le Plateau in Paris. The latter consisted of a survey of Triple Candie projects between 2006 and 2012 — the first. The Hammons and Noland exhibitions were represented by two new advertisements designed by Triple Candie. Flip Viola and the Blurs was recreated. And a number of projects were presented in a series of handmade photo-copy books displayed on shelves.

In 2014,

in relationship to an invitation to produce a project for NICC's storefront space in Brussels, Triple Candie embarked on a multi-year strain of research under the banner, "Let the Artists Die!" This subject was further explored during a guest curator residency in Melbourne, Australia in August 2015.

Fulton Street Vitrine, 2014–5

Beginning in July 2014 until November 2015, Triple Candie curated small anonymous displays in a glass vitrine that it built and installed in an overgrown alley in a residential neighborhood in Center City Philadelphia. The shows, which changed every 3 weeks, were not pre-announced or promoted; knowledge of them was spread via word of mouth.

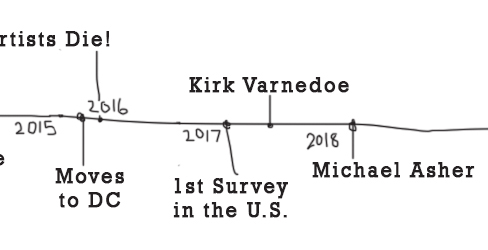

From Philadelphia to Washington, D.C. , First U.S. Survey, and Beyond, 2015–20

Triple Candie's co-directors moved to the District in November 2015, where one of them became Executive Director of a nonprofit contemporary art space. They continue to produce exhibitions on commission for museums and art spaces in the U.S and abroad.

In 2017, the Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover, Massachusetts presented the first U.S. survey of Triple Candie: Throwing Up Bunnies: The Irreverant Interlopings of Triple Candie, 2001-2016. It included partial recreations of the Hammons and Noland shows, a new version of Undoing the Ongoing Bastardization of the Migration of the Negro by Jacob Lawrence (2007/2017), the realization of a previously unrealized project (Harrogate Seven), a new body of work based on Polish playwright Tadeusz Kantor's Let the Artists Die, and a 50-foot-long display that utilized historic American paintings from the Addison Gallery's permanent collection.

Since the survey, Triple Candie has produced two produced projects based on ideas presented to it by others. The first, titled Kirk Varnedoe: In the Middle at the Modern, was on the life and career of the late MoMA chief curator (1946-2003) and his controversial exhibition High & Low: Modern Art & Popular Culture. The project was exhibited in the Telfair Museum's Kirk Varnedoe gallery and acknowledged how Varnedoe's "failures" presaged important changes in the larger art world. The second project, If Michael Asher, was conceived as a series of four Asher-like interventions into the institution and its functions, imagining what Michael Asher (1943-2012) might have done had he been afforded the same opportunity.

Lil Pub Exhibitions, 2021–present

Twenty years to the day after opening its first venue, Triple Candie opened a tiny space (22 sq. ft) in the facade of the former Lil Pub on Pennsylvania Avenue SE, just blocks from the U.S. Capitol Building, and a quarter of a block from the Eastern Market metro station. The projects are unannounced, on view 24 hours a day, and change monthly.